Waiting on the resurrection of the body

Lessons from Simone de Beauvoir, migraines, and Fr. Mike Schmitz

Some days, I just can’t wait for the resurrection of the body.

A big theme in my writing and thinking is the importance of embodiment—and, more specifically, the fact that the pains and struggles and transcendent joys of female fertility offer women a privileged opportunity to confront the interconnectedness of the human body and soul in a visceral way.

I believe all of this, but I still kind of hate experiencing it.

My kids and I were all sick last week (my guess is the flu, though we didn’t get tested), and I’m still struggling with the aftermath. I’ve got a migraine that’s lasted well over a week now, which hasn’t responded to naps and hydration. I’ve been beating it back with Advil and coffee, which have done a number on my stomach (exacerbated by—sorry for the TMI—period cramps). In spite of my periodic resolves to “offer it up,” I’ve been irritable and unproductive and self-pitying.

Which is all to say: woe is me. Having a body kind of sucks sometimes. Everybody knows it, and it’s boring to hear other people complain about it. (Sorry again.)

The funny thing is, just a couple of weeks ago, I was composing a very different Substack post in my head, inspired in part by

’s excellent Fairer Disputations essay, about how strong I was feeling. I’ve been doing a hypertrophy-based heavy weight-lifting program, and loving how it made me feel so empowered and ready to tackle hard things. After several months in which I struggled to make real progress on my book (despite putting in lots of time and effort), I finally felt a sense of mental clarity and created a new structure that works much better. I was doing heavy lifting, both physically and mentally, and loving it. I was a badass. I could do anything I set my mind to, February vibes be damned. And then… here came the flu and migraine and tummy troubles and general woefulness.That’s how it is, being a body-soul composite. There are so many ups and downs, especially when you throw female hormonal fluctuations in the mix. It can be incredibly difficult to discern when to exert your willpower and push through to do hard things. Sometimes, when you do, both your body and mind rise to the challenge, allowing you to stop wallowing and feel a sense of agency that can break through the depressive clouds of self-pity. But other times, all you do is deplete your reserves further, leaving you brittle and tired. Sometimes, the right response is to honor your body’s need for rest.

I loved Dixie Dillon Lane’s recent Public Discourse essay on the seasons of motherhood, as well as my sister-in-law

’s FD piece about a female-centric vision of time-management, pushing back against our cultural obsession with productivity. (Relatedly: don’t miss ’ essay at FD today about the mysteriously productive “nightlife” of motherhood.)Much of the work of motherhood is based on a deeply personal and prudential discernment of exactly what we’re called to do right now. Is this a season of quiet, internal gestation, when we just have to hold on to the knowledge that we are doing important, unseen work? Is it a time of recovery when we need to be gentle with ourselves and gradually replenish our depleted physical and psychological reserves? Or is it time for a push a of productivity, an energetic season of creation, growth, and hard work?

All of these seasons are good and necessary. The danger comes when we try to will ourselves into a different one or resist doing the work that’s asked of us right now.

This is true for all humans, really. It’s just that mothers are so often presented with situations in which their bodies and their bonds with their children make this reality feel more stark and immediate. The stakes are dramatic, even eternal. We are responsible for shaping the souls and bodies of immortal beings, after all.

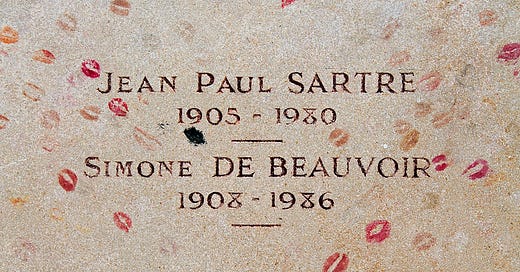

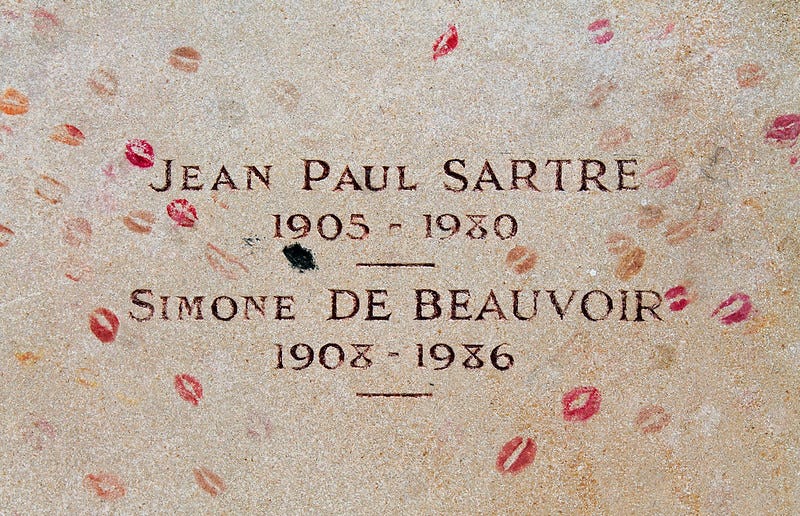

I’ve got an interview out at Public Discourse today with the amazing Abigail Favale that touches on these ideas. As part of my book work, I recently read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, and I asked Abby to help me make sense of it. It’s obviously a brilliant work (though, honestly, it’s also exhibit A demonstrating that everyone needs an editor).

Yet, partly because of her existentialist belief in the need to become a self and achieve “transcendence” through projects, I think de Beauvoir falls into the trap of valorizing the seasons of pushing through, creating and producing through sheer willpower, bodily needs be damned. She’s also deeply scathing about motherhood, which she sees as “slavery to the species,” and the female body in general.

This is how Abby explains it:

AF: You can’t understand The Second Sex without understanding de Beauvoir’s existentialist framework. That framework posits a stark contrast between transcendence and immanence. For her, we don’t really have a nature. We aren’t human beings by default. We have to become human. We have to rise out of our initial state. We have to transcend our animal nature—our immanence, our facticity—by exercising our freedom in the world through creative action.

For her, that’s what it means to transcend. She’s not making an allusion here to any kind of God. It’s just about transcending our immanence and our status as an object in order to become a self-realized subject in the world.

In her framework, she associates transcendence with what we think of as maleness. She associates women with immanence, because she doesn’t see biological processes as capable of accomplishing transcendence.

That’s why she’s so dismissive of motherhood. For her, motherhood is simply repeating human existence. It does not count as transcendence, because human existence isn’t intrinsically meaningful. It has to be made meaningful. So having a baby doesn’t really matter, because that’s not how you realize your own transcendence. And that baby isn’t really human yet either. He or she has to take the initiative later in life to become human. For her, reproduction is this repetitive, almost vegetative process.

SS: She even refers to pregnancy and motherhood as the individual being in slavery to the species.

AF: Exactly. The values of her existentialist framework just map onto male physiology much better than female physiology. So that means she makes the female body a problem. The female body itself—not just how it’s been received in society, but the female body itself—is an agent of women’s oppression. And so, in order to overcome that oppression, women have to have access to things like contraception and abortion.

That way of thinking about what it means to be free has very much taken hold in feminist thought. I think the existentialist framework behind it remains a little bit implicit. But that association—that understanding of freedom as being freedom from femaleness—is very much part of her legacy.

De Beauvoir argues that socialization makes women weaker (both physically and psychologically) than they would be otherwise. I think that, particularly in her own time period, she was right about that. De Beauvoir-inspired feminist pushback helped create a culture in which previously unathletic moms like Rachel Lu and I can throw ourselves into the male-coded world of weight lifting, becoming as strong as we can be, even if we will never benchpress as much as our husbands. Still, even for the fittest woman, there’s no escaping the fact that periods and pregnancy and postpartum recovery and caring for children make it much harder to ignore your body, get shit done, and—at least according to de Beauvoir—become fully human. That leads naturally to her conviction that women need abortion and contraception to achieve equality and autonomy.

But we’ve had legal abortion and easily accessible contraception for decades now, and women are still facing this problem. We’re more educated and accomplished than ever before, and we’re putting off marriage and childbearing later and later. More and more women are actively choosing not to have children. Others are more conflicted, putting off starting a family until after they achieve their educational and professional goals, or just until they find a decent man who’s actually ready to settle down. Unfortunately, they may find that, when they finally decide to try the lock, that door is now closed for good.

For those who do become mothers, the conflict between female embodiment and self-actualization through creative work still rages. I’m currently reading Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch, a novel in which an artist-turned-stay-at-home-mom finds herself transforming into a dog at night. Isolated at home with a two-year-old and a husband who’s gone all week for work, she grapples with feelings most moms must confront: a sense that they’ve lost who they were, that they’ve become someone they don’t know, that their bodies are now in charge in a way that is disconcerting, even frightening.

De Beauvoir doesn’t have a satisfying answer for women like these. Perhaps she would say to put the child in daycare and go back to work, but the mother already tried that, and she couldn’t stand leaving her child crying on the cold linoleum floor. Perhaps she would say that the mother’s suffering is her own fault for choosing to have a child, for choosing to stay mired in the immanence of bodily care for needy children and the subjugation of economic dependence on her husband.

The problem is, the sterile autonomy of the existentialist vision just doesn’t account for the lived experience of being a human being, let alone a female human being or—most of all—a mother. I don’t think contemporary mainstream feminists would ever be as scathing about motherhood as de Beauvoir was. But, for so many decades, the answer women were given really did boil down to fitting themselves into male models of success and self-actualization. No wonder there’s such an anti-feminist backlash, when we think “feminism” means denying our own bodies and babies.

Again, I come back to the body—in all its inconvenience and migraines and cramps, that body that allows us to lift weights and embrace each other and create new life and smell the tops of our newborns’ heads and hear music and see inexpressible beauty, which allows us to live and yet is always inching us closer toward death and decay. Everything in us cries out for immortality, yet we can only achieve joy when we accept the fact of our own weakness and inevitable death.

So that’s why I’m meditating on the resurrection of the body today. Catholicism frankly acknowledges the paradoxical realities that make up our human existence, allowing them to stand, embracing contradictory truths and offering a transcendent revelation that integrates and enhances them.

I’ll let Father Mike Schmitz have the last word here. In episode 136 of the Catechism in a Year podcast, he says:

What is dying? Well, in dying, the separation of the soul from the body happens. The human body decays, and the soul goes to meet God, while awaiting its reunion in the glorified body.

So what is resurrection? What is rising? That “God in his almighty power will definitively grant incorruptible life to our bodies by reuniting them with our souls through the power of Jesus' resurrection,” which is remarkable…. he will change our lowly body to be like Christ's glorious body, into a spiritual body.

And again, how does that happen? … This “how” exceeds our imagination and understanding. It’s accessible only to faith. And yet we recognize this happens right now, this happens at every mass…. Here's the Eucharist, which is made from bread and wine. It just comes from the earth. It is completely ordinary and it's good, right? But it's very normal, very ordinary, from the earth. But when transubstantiation happens, when it's transformed, it becomes something else. It looks like bread. It looks like wine, but it's now something new. It's a new substance. It's a new whole new thing.

And so similarly, you'll get your body back. My guess is it'll probably look like your body, just like Christ resurrected from the dead looked like Jesus, but different, right? New, transformed, some kind of a new, new thing…. If you're male, you will have a male body in eternity. If you're a female, you will have a female body in eternity. You'll have your body in eternity, but transformed.

What's that transformation look like? What does Christ's body look like in eternity? And what will yours look like in eternity? We're looking forward to that. But also we recognize that, because of baptism, we're already participating in this. Paragraph 1002 says that by “virtue of the Holy Spirit, Christian life is already now on earth a participation in the death and resurrection of Jesus.” And so paragraph 1003 says, “United with Christ by baptism, believers already truly participate in the heavenly life of the risen Christ.” But it remains hidden, right? And yet at the same time, we have been incorporated into the body of Christ. And when we rise on the last day, we also will appear with him in glory.

Because of that, we treat our bodies differently. And because of that, we treat other people's bodies differently, knowing that your body's not just a husk, right? Your body's not just a shell, it's not a cage, it's not a trap. It's not arbitrary. You are your body. Your body is you. And your body is destined to endure in eternity when you get it back in the last day again, either to glory in heaven or to eternal shame in hell. And because of this, we are invited—we're commanded, in fact—to glorify God in our body, to recognize that other people have a dignity.

Not just their soul, not just their intellect. They have a dignity in their body. How we treat other people's bodies matters. That if you are your body, what you do with your body matters.

And so we conclude with this quote from St. Paul's letter to the Corinthians: “the body is meant for the Lord and the Lord for the body.” The body's not a bad thing, it's a good thing. And God raised the Lord and will also raise us up by his power. “Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ? You are not your own.” So glorify God in your body right now, wherever you're listening to this… Whether you're driving in your car, walking, maybe out for a run, maybe you're stuck in your bed, maybe you're sick, maybe you're unable to move your body, recognize this.

The Lord will give you a resurrected body that will be able to move, that will be able to run, will be able to jump, will be able to do all the things you wish your body could still do. That body is coming, I'm telling you right now. This is what we believe and we profess and we proclaim: that resurrected body will be given to you. But right now, even if all you can do is lay in a bed, even if all you can do is sit in your car right now, even if all you can do is limp, everything you do in your body can glorify the Lord. Just even scratching your face, even just blinking, everything you do can glorify the Lord.

So blink for the Lord's glory. Walk for the Lord's glory. Smile at someone for the Lord's glory. Lay in that bed and experience a lack of strength in that body and let that be for the Lord's glory. Everything we do in our body is meant to be for His glory. As St. Paul says, “glorify God in your body no matter what you do.”

That's what we're praying for today.

Can’t wait to read that conversation between you and Abigail! I love when I have something like that saved for naptime:)

I just finished Nightbitch and I thought it was original and profound.

Thanks for noting my piece, Serena! So glad you liked it. I have your conversation with Abigail Favale noted to read ASAP!